Half-a-billion-year-old fossilised brain in a tiny sea creature defies textbooks

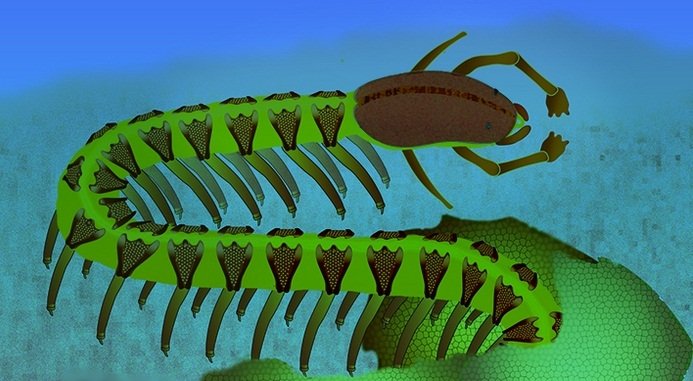

Half-a-billion year old fossilised brain in a tiny sea creature defies textbooks.(photo:Nicholas Strausfeld/University of Arizona)

New York, Nov 26

Fossils of a tiny sea creature that died more than half a billion years ago may compel a science textbook rewrite of how brains evolved.

A study published in Science has revealed a 525-million-year-old fossil of a tiny sea creature with a delicately preserved nervous system, solving a century-old debate over how the brain evolved in arthropods, the most species-rich group in the animal kingdom.

"To our knowledge, this is the oldest fossilised brain we know of, so far," said Nicholas Strausfeld, a Regents Professor in the University of Arizona's Department of Neuroscience.

Strausfeld and Frank Hirth, a reader of evolutionary neuroscience at King's College London, provide the first detailed description of Cardiodictyon catenulum, a wormlike animal preserved in rocks in China's southern Yunnan province.

Measuring barely half an inch (less than 1.5 centimetres) long and initially discovered in 1984, the fossil had hidden a crucial secret until now: a delicately preserved nervous system, including a brain.

Cardiodictyon belonged to an extinct group of animals known as armoured lobopodians, which were abundant early during a period known as the Cambrian when virtually all major animal lineages appeared over an extremely short time between 540 million and 500 million years ago.

Lobopodians likely moved about on the sea floor using multiple pairs of soft, stubby legs that lacked the joints of their descendants, the euarthropods - Greek for "real jointed foot."

Today's closest living relatives of lobopodians are velveted worms that live mainly in Australia, New Zealand and South America.

"This anatomy was completely unexpected because the heads and brains of modern arthropods, and some of their fossilised ancestors, have for over a hundred years been considered as segmented," Strausfeld said.

"From the 1880s, biologists noted the clearly segmented appearance of the trunk typical for arthropods and basically extrapolated that to the head," Hirth said. "That is how the field arrived at supposing the head is an anterior extension of a segmented trunk."

"But Cardiodictyon shows that the early head wasn't segmented, nor was its brain, which suggests the brain and the trunk nervous system likely evolved separately," Strausfeld noted.

The findings also offer a message of continuity at a time when the planet is changing dramatically under the influence of climatic shifts.

"At a time when major geological and climatic events were reshaping the planet, simple marine animals such as Cardiodictyon gave rise to the world's most diverse group of organisms - the euarthropods a" that eventually spread to every emergent habitat on Earth, but which are now being threatened by our own ephemeral species," said the researchers.

--IANS